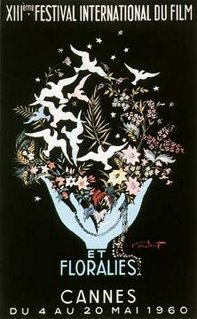

Miller On The Cannes Jury, 1960 (PT. 2)

“I’m excited by film. It’s one of the freest, most effective means of expression. Especially in the realm of dream and fantasy! What wonders, what joys it may hold in store for us! Some day film may replace literature.”

“I’m excited by film. It’s one of the freest, most effective means of expression. Especially in the realm of dream and fantasy! What wonders, what joys it may hold in store for us! Some day film may replace literature.”(Henry Miller, quoted in Henry Miller, Happy Rock by Brassai [1], p. 30)

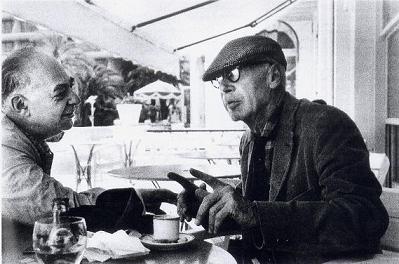

The president of the 1960 Cannes Film Festival, Georges Simenon, suggested that Henry Miller spent more time playing Ping-Pong than watching films, as was his obligation as a member of the jury (see previous post). Miller, 69, complained to his friend Brassai of his exhaustion at viewing so many long films in poorly ventilated halls.

“I deplore the sadness, the excessive length of so many films--two or even three hours of viewing—for the most part slow, incoherent, weepy, morose.” ([1], p. 60) Were it not for the exciting feeling that he was entering “a new era” in his life, Henry admitted that just five years ago he would have considered a full day of film-viewing “a tremendous waste of time.” ([1], p. 31).

But Miller also fancied himself an “old film buff” ([1], p. 30). Though not thoroughly impressed with that year’s line-up, a few of the cinema selections made an impression on him:

THE INTERNATIONAL FLAVOURS OF CINEMA

Miller observed the fact that films from different countries tend to have their own temperament and atmosphere: “Everything from the north is slow, heavy, sometimes childish. The Slavic films, though often bad, are always full of humanity.” ([1], p. 60).

BERGMAN'S THE VIRGIN SPRING

"Set in medieval Sweden, it is a revenge tale about a family's response to the murder of their daughter."(continue reading this synopsis at Wikipedia).

"Set in medieval Sweden, it is a revenge tale about a family's response to the murder of their daughter."(continue reading this synopsis at Wikipedia).Miller: "The Virgin Spring is very spare, very strong, based on an old ballad. It's the story of a young girl who is carrying candles to the Virgin Mary. On the way to the church, she is raped and murdered by three shepherds. The rape scene in the forest is of an almost unbearable brutality. I've never seen anything like it. But the film is more poetic than realistic, and very pure, almost chaste, in spite of the rape." ([1], p. 86)

The Virgin Spring was given recognition for direction at Cannes, known as the 'Special Homage' (ref) or 'Special Mention' (which, as far as I can tell, is a verbal acknowledgement instead of a physical award).

MELINA MERCOURI IN NEVER ON SUNDAY

MELINA MERCOURI IN NEVER ON SUNDAY"Just between us, " confided Miller to Brassai, "no actor or actress seems to deserve the prize. Oh well, yes, perhaps Melina Mercouri." ([1], p.84). In Never On Sunday, Mercouri played a vivacious, free-spirited Greek prostitute. [view a clip of the film on YouTube]. Miller's appreciation was shared: Mercouri was awarded a Best Actress prize at Cannes.

ICHIKAWA'S KAGI (aka ODD OBSESSION)

According to Henry Miller: A Life (Robert Ferguson), Kagi was Henry's favourite film (he had voiced his approval to the editors of the Henry Miller Literary Society) (p. 337). The film revolves around "an aging lecher whose strategy is to restore his virility by making himself jealous" -- read this contemporary account of the Cannes screening in Time magazine.

Kagi was awarded a Jury Prize at Cannes, as was Antonioni's L'Avventura.

FELLINI'S LA DOLCE VITA

The winner of the big prize at Cannes, the Palme D'Or, was Fellini's La Dolce Vita. According to the memoirs of Georges Simenon, the jury had been split between this film and Antonioni's La Notte. "I am enthusiastic over La Dolce Vita," writes Simenon, "which has created something of a scandal. Thanks to the vote of Henry Miller, who doesn't have an opinion and has decided to vote as I do, and one other juror, La Dolce Vita wins." (Intimate Memoirs by Georges Simenon, p. 476).

A few days before this conclusion, Henry spoke to Brassai about the film: "Fellini's film also lasts three hours, but it doesn't seem long. It moves faster than the others, is teeming with characters and events. You hardly ever get bored with it." ([1], p. 60). "What is marvelous in this film is the satirical depiction of the tabloid press. The obsessive presence of the pack of paparazzi in every circumstance." ([1], p. 61).

A few days before this conclusion, Henry spoke to Brassai about the film: "Fellini's film also lasts three hours, but it doesn't seem long. It moves faster than the others, is teeming with characters and events. You hardly ever get bored with it." ([1], p. 60). "What is marvelous in this film is the satirical depiction of the tabloid press. The obsessive presence of the pack of paparazzi in every circumstance." ([1], p. 61).About La Dolce Vita: IMDB, Wikipedia, Roger Ebert. View clips from La Dolce Vita on YouTube: 1, 2, 3, 4, and the famous fountain scene.Here's a list of all films in competition at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival. And the films that won. Here's the same kind of information at IMDB, but with links to all films and people, including the jury members.

The website's description of this lot contains several quotes taken from these letters, circa 1973-78:

The website's description of this lot contains several quotes taken from these letters, circa 1973-78:

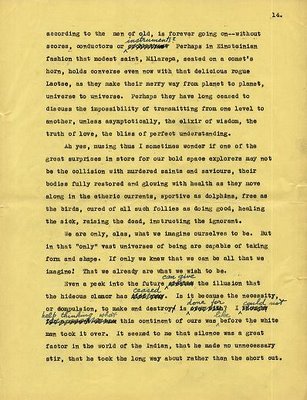

This copy doesn't include any editorial corrections; only corrected typos and a couple of proofed spelling errors. The batch is being offered for US $2700.

This copy doesn't include any editorial corrections; only corrected typos and a couple of proofed spelling errors. The batch is being offered for US $2700.

This collection is selling for US $3000.

This collection is selling for US $3000.